Overall, although the included studies showed a higher level of satisfaction among women who had midwife-led care compared with those who did not, the reviewers could not identify which aspects of care increased women’s satisfaction.

While nine studies reported on maternal satisfaction, there was ambiguity around the concept of satisfaction, and inconsistency in the tools used to measure satisfaction. However, a lack of consistency in measuring women’s satisfaction means that the Cochrane review Midwife-led versus other models of care for childbearing women was only able to report on satisfaction outcomes using a narrative approach.

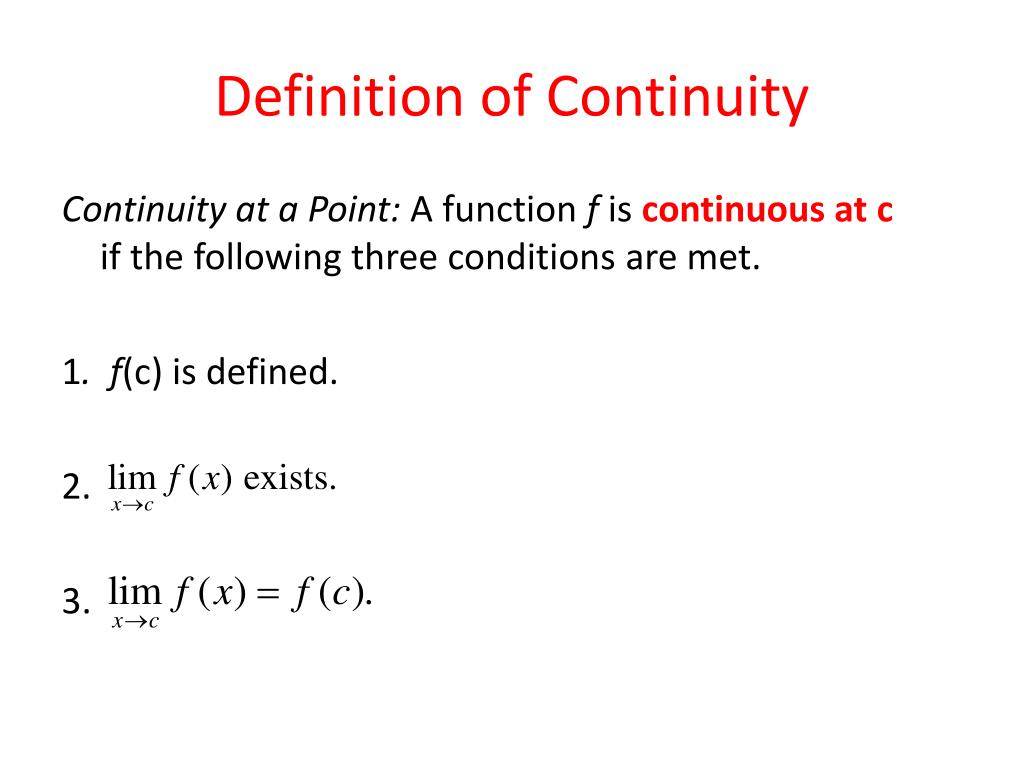

#Continuity perception definition trial

Many of the RCTs of midwife-led care report increased satisfaction associated with being allocated to the midwife-led care trial arm. These findings confirm those of other RCTs of midwife-led care, suggesting that these models reduce interventions without jeopardising health outcomes. We conducted a randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing caseload midwifery care with standard care and found that women allocated to caseload midwifery were less likely to have a caesarean birth, analgesia during labour, and an episiotomy that fewer infants were admitted to the special care nursery and that mother and infant safety outcomes did not differ statistically between the study groups. In the caseload model women are cared for by a primary midwife throughout pregnancy, birth and the early postpartum period. Trial registrationĪustralian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN012607000073404 (registration complete 23rd January 2007).Ĭontinuity of carer has been strongly recommended and encouraged in maternity services in Australia, and many hospitals have responded by introducing caseload midwifery. Conclusionįor women at low risk of medical complications, caseload midwifery increases women’s satisfaction with antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care. Compared with standard care, caseload care was associated with higher overall ratings of satisfaction with antenatal care (OR 3.35 95 % CI 2.79, 4.03), intrapartum care (OR 2.14 95 % CI 1.78, 2.57), hospital postpartum care (OR 1.56, 95 % CI 1.32, 1.85) and home-based postpartum care (OR 3.19 95 % CI 2.64, 3.85). The response rate to the two month survey was 88 % in the caseload group and 74 % in the standard care group. Two thousand, three hundred fourteen women were randomised: 1,156 to caseload care and 1,158 to standard care.

A secondary analysis explored the effect of intrapartum continuity of carer on overall satisfaction rating. The primary analysis was by intention to treat. Data for this paper were collected by background questionnaire prior to randomisation and a follow-up questionnaire sent at two months postpartum. Women allocated to standard care received midwife-led care with varying levels of continuity, junior obstetric care, or community-based general practitioner care. The caseload model included antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care from a primary midwife with back-up provided by another known midwife when necessary. Women were randomised to caseload midwifery or standard care. Pregnant women at low risk of complications, booking for care at a tertiary hospital in Melbourne, Australia, were recruited to a randomised controlled trial between September 2007 and June 2010. The aim of this paper is to evaluate the effect of caseload midwifery on women’s satisfaction with care across the maternity continuum. Continuity of care by a primary midwife during the antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum periods has been recommended in Australia and many hospitals have introduced a caseload midwifery model of care.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)